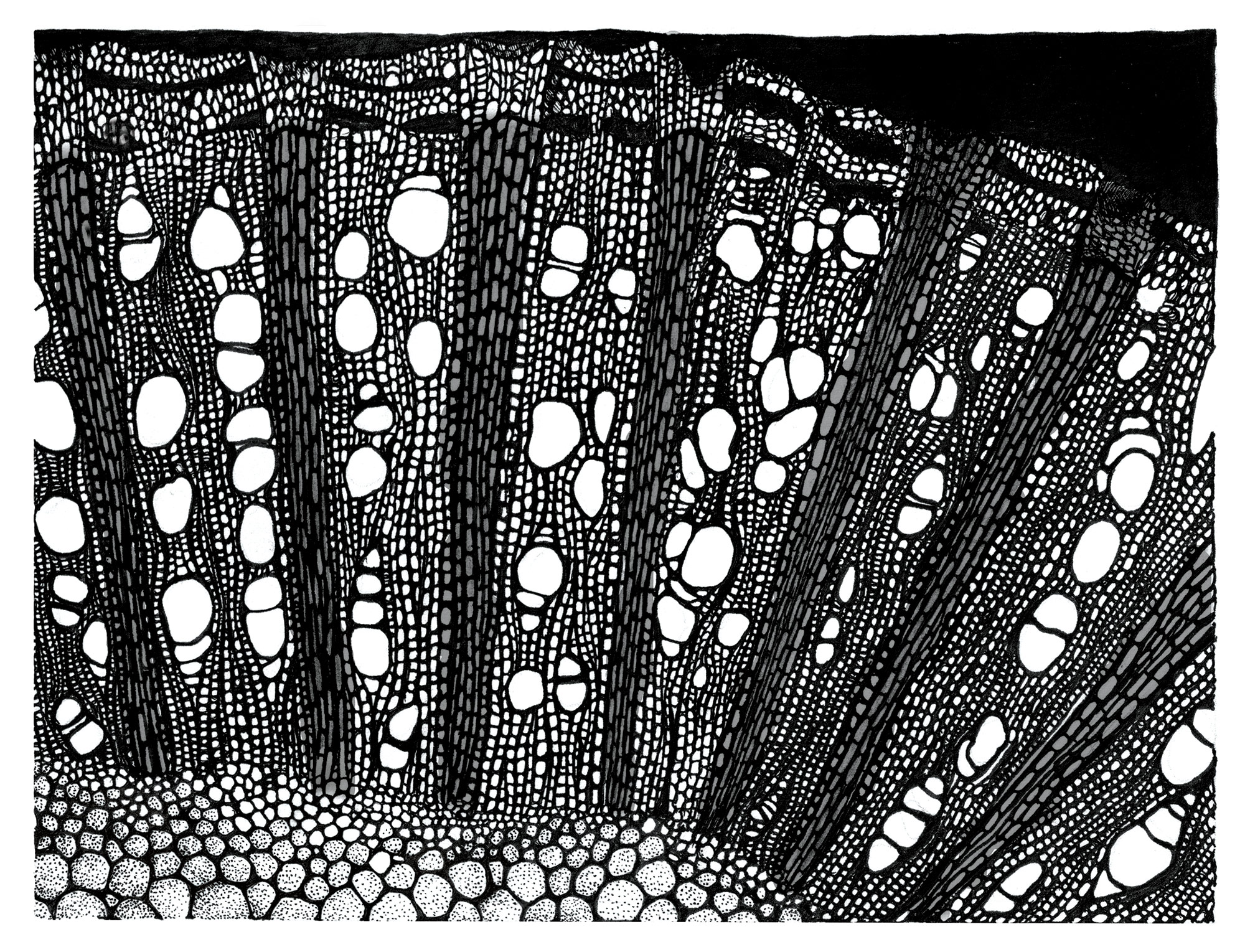

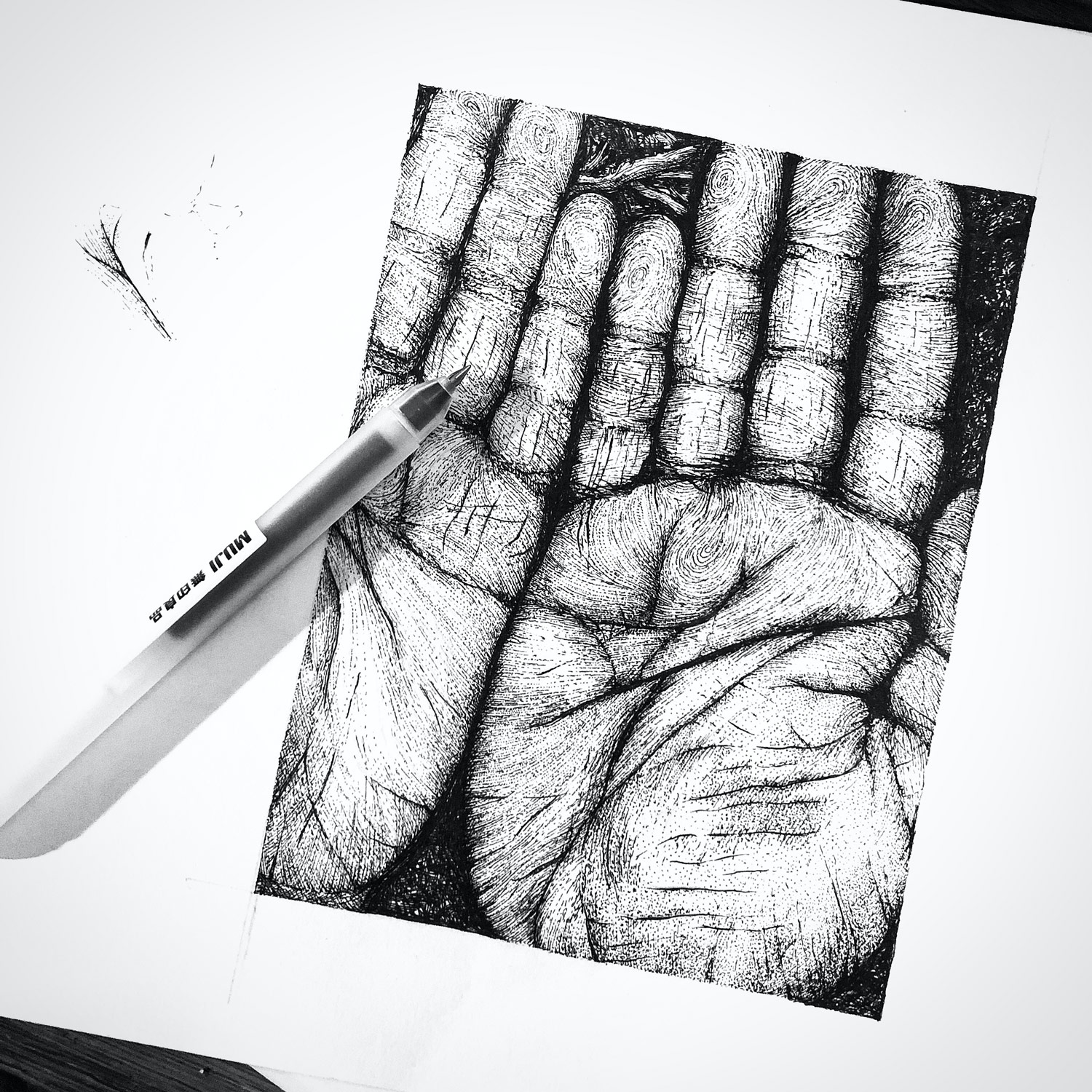

If you’ve spent much time in any trendy London wine shops, you’ll be used to some pretty eye-catching bottles. Westwell’s are no exception. Based outside of Ashford in Kent, Westwell has made a name for itself by producing an idiosyncratic range of wines labelled with beautiful black-and-white pencil etchings of the vineyard’s soil, cross sections of vine wood, and close-ups of grape skins in fermenting wine.

Despite lockdowns preventing in-person trips to England’s idyllic vineyards, the magic of technology allowed me to catch up with Adrian Pike, the Managing Director and Winemaker at Westwell, and find out a little more about his journey into the wine industry.

The best winemakers always have a good backstory. Adrian’s is a doozy. If you have ever enjoyed the music of Bloc Party, Hot Chip or Florence and the Machine, then you have Adrian to thank. Back in 1998, he co-founded Moshi Moshi Records, the record label that launched those artists’ careers. Fast forward to 2014 and Adrian was growing tired of the music industry. “I realised my passion for music had dimmed quite a bit and I was getting really into wine at the time and was actually considering moving to France”, he explains.

“I had met Jim Clendenen (winemaker of Santa Maria Valley’s Au Bon Climat) at a tasting and he told me, ‘you have to go to Burgundy.’” But it was a chance encounter with an English wine that opened Adrian’s mind to the opportunities on his doorstep: “I was having lunch at Arbutus in Soho and tried Will Davenport’s Horsmonden Dry. I was amazed you could make something like that in England. It had these beautiful English flavours but was really precise and balanced. So I never ended up going to France. I phoned Will and asked if I could work for him.” After a brief stint volunteering at Forty Hall Vineyard in Enfield, Adrian completed his first vintage with Will in 2014 and stayed working in the winery afterwards. At the same time, he enrolled in a winemaking course at Plumpton College. “There was a real contrast between working with Will and studying at Plumpton”, Adrian explains. “You need to understand the science behind winemaking but there’s so much you can learn by talking to a winemaker about what they’re looking for in the grapes, and how they achieve certain textures and flavours in the wine.”

A few years later, Adrian was looking for a vineyard of his own and stumbled across Westwell, outside Ashford in Kent. “It’s just kind of the perfect site”, he says. “It’s on the south side of the North Downs and protected from frost by the trees planted above it along the Pilgrims Way.” The original 13-acre vineyard features Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay along with Ortega, a Germanic variety.

Since taking over the estate in 2017, Adrian and his Vineyard Manager, Marcus Goodwin, have planted a further 20 acres of vines while painstakingly cutting the use of artificial herbicides.“You’re a custodian of a living plant”, he explains, “and we want soil and plant health to be as strong as possible, we’re concerned that by an over-reliance on herbicide you damage the ability of the soil to sustain the plant and the plant to fight disease. In the long term we think it’s more sustainable to move away from synthetic sprays and our current plan will help us achieve that soon.” But he stresses that they are taking a pragmatic approach. “When we took over, the site was conventionally farmed and in the first year we did exactly the same thing as the previous owner so we could see what was going on in the vineyard. Each year, we divide the site into four quarters and try different treatments on each. Now we’re using 75% fewer sprays across the vineyard.” That’s no mean feat. In a wet climate like Britain’s, diseases like mildew and botrytis (a fungal disease) can spread rapidly through a vineyard and weeds grow thick and fast, competing with the vine for resources. As a result, most of the UK’s vineyards rely on fungicides and herbicides. Only 3% of England’s vineyards are registered as organic, meaning they use no artificial sprays at all (although certain organic sprays like copper sulphate are used).

This pragmatism extends to the winery. Most of the wine in the UK is made using cultivated yeast grown in a laboratory. This has the advantage of providing reliable results and gives the winemaker more control over the process of fermentation. But using wild or ‘indigenous’ yeast that can be found living on the skins of the grapes and in the winery itself, “gives this real energy and liveliness to the wines”, according to Adrian.

Using indigenous yeasts is a hallmark of minimal intervention or ‘natural’ winemaking, although it’s a label that Adrian isn’t entirely comfortable with: “I don’t see the point in adding anything to a wine if you don’t need to but we’re not ‘minimal’; it implies you just press the grapes and forget about it. But we’ve been tasting through the grapes in the vineyard to find the ones that have ripened the most and we’re checking the sugar levels and acidity of the grapes constantly. We’re not minimal intervention, we just don’t add much.”

Adrian is also happy to use small amounts of sulfur dioxide to prevent unwanted bacteria causing ‘off’ flavours in the wine. “We don’t want the wine to spoil in the bottle”, he reminds me. He’s also keen to point out that the still wine used to make his sparkling wines such as Pelegrim use some commercial yeast because of the need for consistency.

Of the original vineyard’s 13 acres, four were planted with Ortega. Adrian has a particular soft spot for the variety which he was familiar with from his time working with Davenport. “It was a grape that really leapt out at me. I love the orange blossom notes you get from it”, he explains. What’s more, Ortega loves the English climate and, although susceptible to botrytis, it “ripens and crops really well”. The grape has proven to be particularly well-suited to skin-contact. Sometimes called ‘Orange Wine’, the style is made by macerating the skin of white grapes in fermenting juice, which adds extra colour, flavour and a touch of tannin to the finished wine. Adrian points to La Stoppa, based in Emilia-Romagna and The Hermit Ram, from Canterbury in New Zealand, as his favourite producers of skin-contact wine. “I’ve been fascinated by the style ever since I tried it”, says Adrian. It’s a tricky one to master”, he admits. “We’ve learnt that leaving the skins in contact with the finished wine actually softens the tannin.”

Adrian is keen to emphasise the importance of ageing wines properly in the winery: “There’s a lot to be said for leaving your wines and giving them time before releasing them.” This is especially important given that many of the wines are unfined and unfiltered which means they need time to clarify and stabilise. Of the four Ortega wines currently on sale, one is aged for nine months in barrel, another in clay amphora for a year, and a special release aged for two years, first in amphora and then in barrel.

While still wines are important to Westwell, they are, first and foremost, a Sparkling Wine producer. The process of making Traditional Method Sparkling Wine can take years. Of course, that means that the true Westwell sparkling wines, made entirely by Adrian and his team, are only on the horizon. The Pelegrim, Westwell’s flagship sparkling wine, is now based on the 2017 vintage, the year Adrian took over, but still includes reserve wines made by the previous owner, John. “John was a really good winemaker”, explains Adrian. “He spent a lot of time creating incredible reserves, and that’s still what we’re using to make some of our sparkling wines.” The results of these reserves have been some strikingly special releases, including a complex and savoury Blanc de Blancs 2011 and a rich and textured Blanc de Noirs 2013.

Adrian also has an innovative single varietal Pinot Meunier in the pipeline: “[It’s] a blend of three vintages but bottled while the wine from the third vintage was still fermenting.” The idea came from a visit to Domaine de la Pinte, a biodynamic estate in the Jura, and the method bears some similarity to how a Pétillant Naturel wine is made. While the wine still has 18 months to age on its lees before its release, you can already tell that it’ll be a true Westwell wine: a curious blend of experimentalism, pragmatism, patience, and fun. “How fizzy will it be”, I ask, “more like a traditional method sparkling or a Pét-Nat?” “We’ll find out when we open it”, Adrian laughs.

All photos & visuals with thanks to Westwell

Westwell Pelegrim NV

Grapes: Chardonnay, Pinot Noir & Pinot Meunier

This is Westwell’s flagship sparkling wine. Made using the traditional method, the current release is the first to be based on Adrian’s grapes, picked in 2017. Added richness comes from 36 months of lees ageing and the addition of reserve wines, which make up 20% of the blend.

The nose is generous with baked orchard fruit and raspberries sitting on top of a biscuity, slightly toasty base. The palate features ripe orchard fruit and a smattering of red berries, and is underpinned by a nice whack of acidity that keeps the wine in balance.

In a recent consumer tasting that pitted English Sparkling Wine against Champagne, the Pelegrim fared well, coming out on top alongside Nyetimber and Hambledon when served blind. When the wines were revealed and poured again, the tasters seemed to reverse their preferences, with most of the English wines falling to the bottom. All, that is, except Pelegrim, which maintained a position near the top. “Our crowning glory!”, jokes Adrian.

Westwell Ortega 2019

Grapes: Ortega

Westwell’s purest expression of Ortega, this was fermented in stainless steel tanks at cool temperatures to make a wine that is fresh and crisp.

“This wine is designed to go with seafood”, explains Adrian. “We’re trying to see if we can turn it into a kind of English Albariño.”

The nose is bright and aromatic with flavours of pears, fresh peaches, and white blossom.

On the palate, it’s wonderfully fresh with crisp acidity supporting lots more orchard fruit and floral flavours.

Westwell Ortega Skin-Contact 2019

Grapes: Ortega

This is Westwell’s ‘entry-level’ skin-contact wine. Three quarters of the grapes are destemmed, and the remaining quarter is added as whole bunches to a stainless-steel tank. It is fermented for three weeks on the skins using wild yeasts. The wine is then pumped off and aged in old oak barrels for nine months. Finally, it is bottled without fining or filtration.

The nose is a delightful mixture of fresh peaches and apricots, white blossom, and orange pith and peel.

The palate features fresh acidity and plenty more stone and citrus fruit flavours. Most notably, the skin-contact gives the wine a very gentle touch of tannic grippiness.

This is a great wine to try if you’re looking to dip your toe into the wacky world of Orange Wine.

Westwell Field Blend 2018

Grapes: Pinot Noir & Chardonnay

Across the country, 2018 was a record-shattering year for yields. This gave many winemakers enough grapes to experiment with, but also created its own problems. “Trying to get grape juice into tank was like Tetris”, explains Adrian.

This field blend was the result. Made from Burgundy clones of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, grown on three adjacent rows, the grapes were fermented together in stainless steel tanks and bottled the following spring without fining or filtration.

The result is a pale-coloured wine bursting with fresh strawberries and redcurrants, hard boiled sweets and a touch of dried herbs.

It’s light-bodied with mouthwatering acidity and almost non-existent tannin. It benefits from being served slightly chilled, perfect for drinking in the garden or park when this year’s warm weather appears.